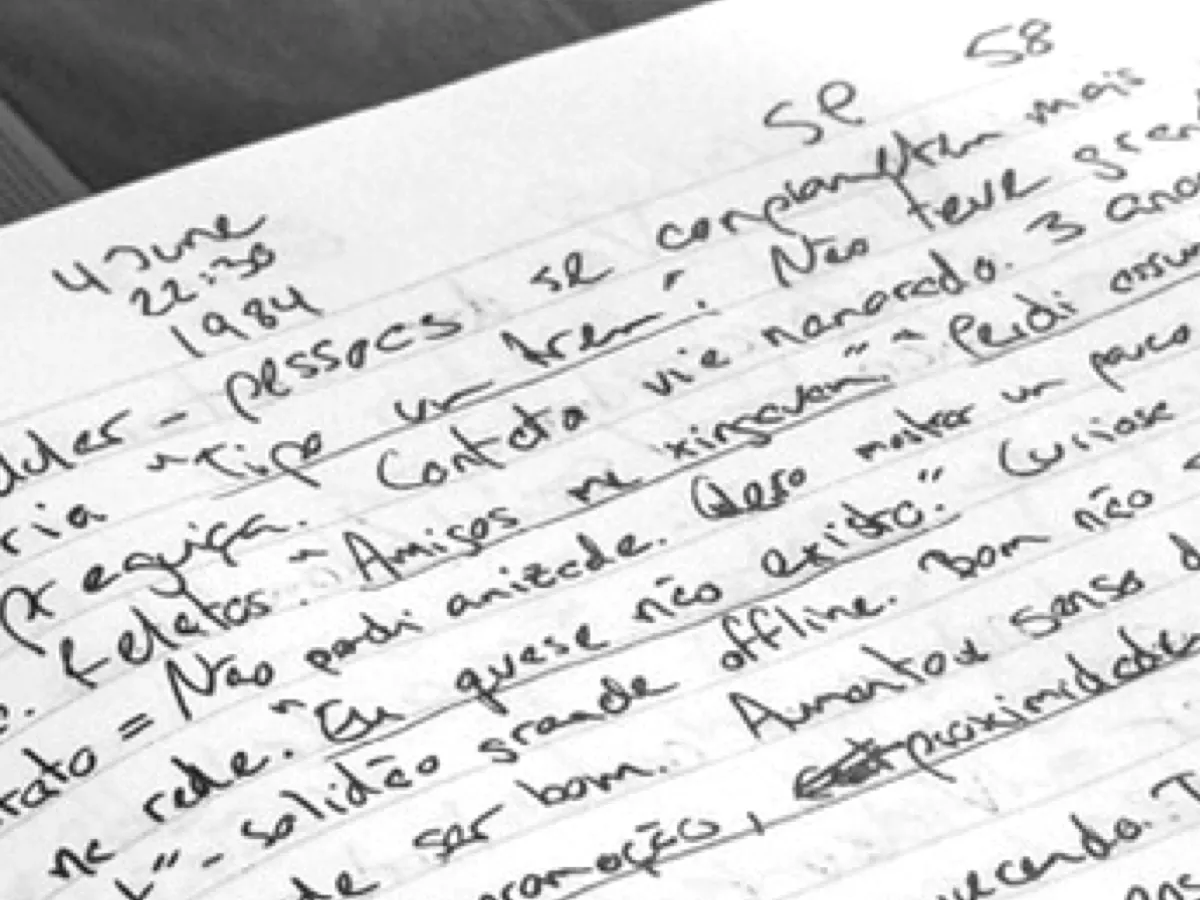

When I did not have a phone, my friends treated our appointments like they were catching a train says Amanda, who recently acquired a smartphone after three years of not owning one. They had to be on time because I had no way of finding out if they messaged me.

My friends would curse me. They said it was impossible to keep me in the loop. Without social media or instant messaging it was like she did not exist among certain groups. It became more difficult to have conversations in real life because we did not know what the other person had been up to.

Amanda did not lose friendships or miss real-world events because of the self-imposed exile. Despite causing grief to some, she managed to strengthen the relationships with others, through elaborate email chains with close friends and long Skype calls with her family. These conversations kept her abreast of life back home throughout the three-year artist residence program abroad. Having recently returned to São Paulo when we meet at a late-night diner, she is still getting used to having a smartphone in her life.

It’s like you don’t exist if you’re not on social media. Nobody sees your work, friends don’t know what you’ve been up to, people don’t know where you are. Of course it can be liberating to reclaim your focus, to strengthen your attention and dive deeply into work – but after it is done, the work benefits from being shared – and the internet excels at promoting novel ideas. Amanda’s work after the residency was brilliant, but did not quite reach her intended audience because having lived offline so many years, there was no natural outlet through which to promote the work.

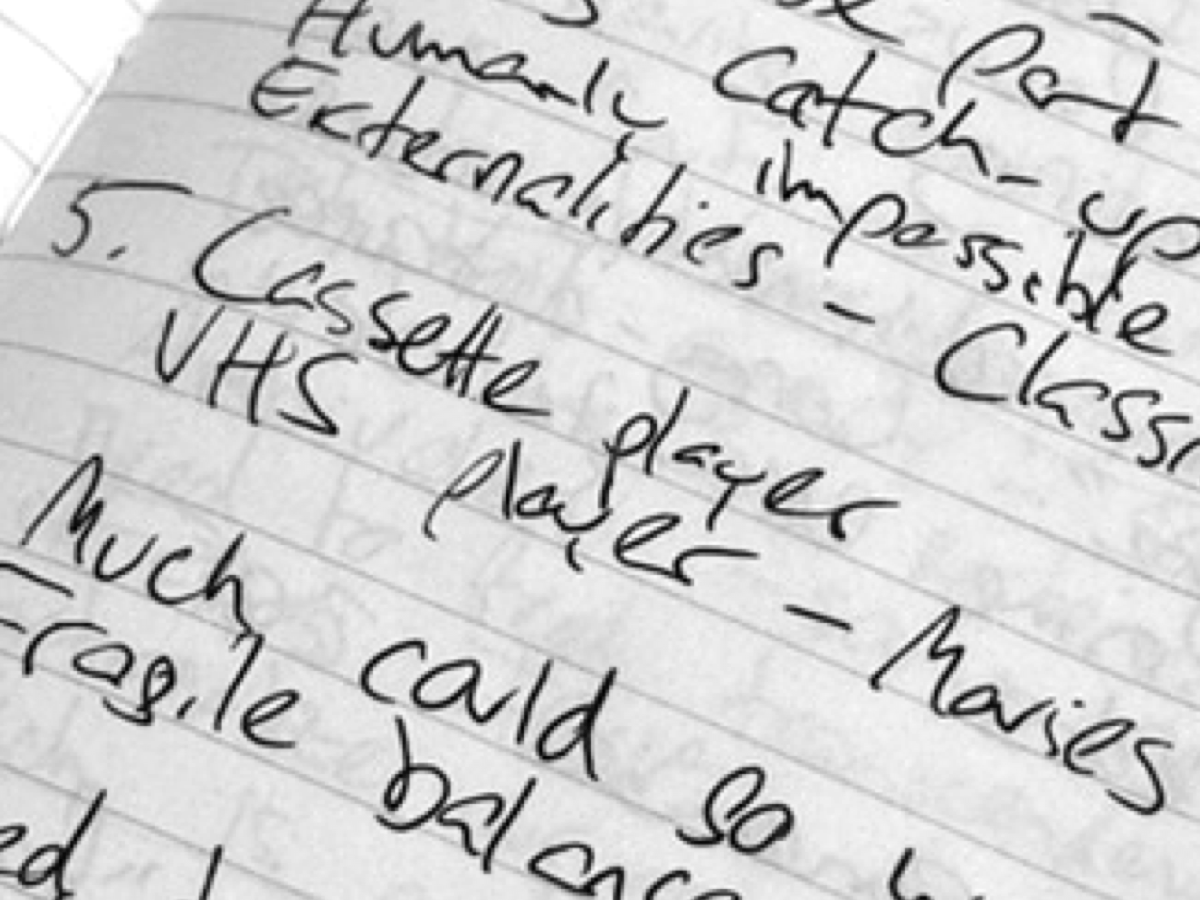

Surely not everything needs internet promotion to be effective. In fact, much beauty is created without the need to be experienced – like a monk chanting mantras from the mountaintop, knowing people below need not hear it to be positively affected – but unlike the monk, Amanda pays rent, and requires grants and other support systems to continue sharing her gift with the world.

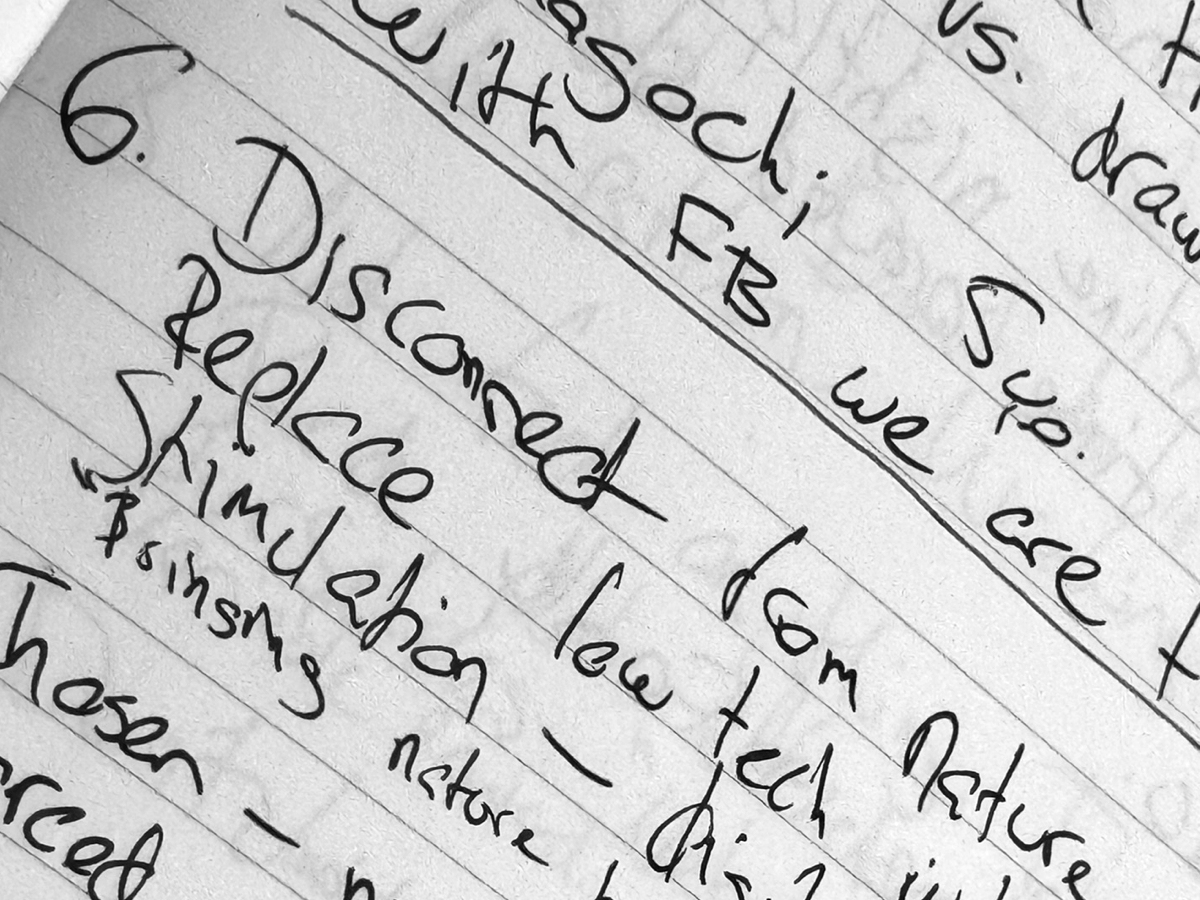

In fact, if you work with any form of imagery like photography, fashion or visual arts, you are virtually required to have an online presence on places like Instagram. Journalists barely exist outside of their Twitter profiles, touring musicians rely almost exclusively on Facebook to promote their acts, and many families abroad only keep in touch because of WhatsApp groups.

It is easy to shun these platforms, calling them insidious and manipulative – which is a fair characterization – but it is difficult to integrate them into our lives without causing harm. Some people are perfectly capable of living without social media and happily concentrate interactions with other people face to face, or email and occasional telephone conversations. These people usually have jobs that require a certain detachment from society, like writers or professors, who generally benefit from maintaining distance from others.

Other people feel social media has actually enriched their lives exactly because it enables a light-touch communications protocol with distant yet important others in their lives. Some genuinely care about their childhood friend’s baby pictures, or enjoy receiving silly memes in the family WhatsApp group – to them, social media enriches both lived experience and relationships.

Acknowledging the negative effects of excessive social media use is easy. Just about everyone I speak with recognizes the ambivalent co-dependence we develop with our personal technology. There is no doubt whether technology robs us of valuable moments or demolishes our attention – that much is apparent. The question is how how do we arrange our technologies in such as way that minimizes the negative effects, like social polarization and the reverberation of violent discourse – while strengthening the effects that positively serve society.

Me and my smartphone have a deal says Amanda, I am to it what it is to me. They are equal partners but she gets the last word. Neither scorn nor adoration, Amanda allows each situation to dictate the response.

She regularly switches her smartphone off, ideally nightly, keeping the late night and early morning hours offline whenever possible. It feels like I removed an organ when the phone is off, but being offline feels like a healthy form of solitude, allowing me to be with myself.

Asked how technology could serve us better, she claims we should know when to say no to technology and that someone should write about etiquette in the digital age, because everyone is being affected by these changes, everyone complains about the state we have made for ourselves – especially in Brazil where work is regularly commissioned via WhatsApp. Entire project briefings and job scopes are frequently texted (or worse, sent as audio messages) to suppliers, who have to stay on top of messaging apps to remain in the loop. Digital illiteracy, she says, causes our attention to fragment and makes us lose touch with one another.

She calls the years offline her personal Tibet, an excursion into the unknown without leaving home. Perhaps one requires three years offline to fully appreciate the role smartphones have in our life, or perhaps we can learn from those who have climbed the mountain before us.